By Jean Haggerty

ImpactAlpha, July 15 – Evidence of unsustainable value creation and neglect mar Appalachia’s coal country. But the region is determined to cut a path that shows how investing in people, communities and innovation can accelerate an equitable transition to a post-coal economy.

In part two of ImpactAlpha’s series on Appalachia’s post-coal future, three projects offer a potential roadmap for other communities looking to diversify away from coal (see, part one, “Seeding Appalachia’s sustainable future with public and private capital“). The tech-driven projects also begin to showcase investable opportunities in the region’s sustainable future.

Local innovators are testing new technologies and demonstrating alternative uses for mine sites. The projects aim to unlock new value by cleaning up coal-polluted waterways, harnessing solar energy and attracting new businesses, and helping the region transition to a more local, sustainable food system.

For early funding, the projects have tapped the Abandoned Mine Land Pilot Program, a federal grant program designed to help Appalachia’s coalfield communities think collectively about a future without coal.

“[The legacy of coal mining] indirectly impacts everything in the state,” says Fritz Boettner of Sprouting Farms, a West Virginia nonprofit that supports sustainable farm businesses. Boettner is project lead on a new solar-powered aquaponics facility in Kermit, West Virginia. “The economic ecosystem of mines is so much more than the mine.”

Pollution to paint

An effort is underway to turn a contaminant found in coal mine-polluted water into a valuable commodity. The first project involves harvesting iron oxide from a creek impacted by ‘acid mine drainage’ – the highly acidic runoff from mining activity – and transforming it into a high-quality paint pigment using a patent-pending process.

“None of us started this project looking to make paint,” says Michelle Shively of Rural Action, a nonprofit working in Appalachian Ohio. “We wanted to clean [Ohio’s] Sunday Creek.”

Along the way a unique partnership between two Ohio University professors and Rural Action was born.

A few years ago, Dr. Guy Riefler, chair of civil engineering at Ohio University, started working with Rural Action to create technology for pulling iron oxide from acid mine drainage-polluted water. Later, John Sabraw, chair of painting and drawing at the university, joined the project to help the team create high-quality ochre, red and violet paints with the extracted iron oxide.

Acid mine drainage-impacted water, or AMD-impacted water, is a toxic legacy of coal mining. AMD is the main pollutant of surface water in the US’s mid-Atlantic region. The patent-pending process for harvesting iron oxide also returns clean, pH-adjusted water back to the creek.

“[Iron oxide] is a good metal to pull out,” says Shively, noting that there is also a good market for it. In theory, the federal and/or state agencies could use the process to clean AMD-impacted water, and coal companies could use it to extract iron oxide on-site. “Instead of viewing it as a waste product, [coal companies] can look at it as a commodity,” she says.

To help fund the construction of a full-scale iron oxide extraction facility in Millfield, Ohio, next year, the project’s collaborators started a Kickstarter initiative to sell 500 tubes of paint produced at their pilot location in Corning, Ohio. Portland, Oregon-based Gamblin Artist Colors, which conducted tests on the pilot project’s pigments, also produced the paints for its Kickstarter drive.

“The amount of paint that we will be able to produce each year far exceeds the needs of the art market,” Shively says. Other markets for the project’s end product exist, however. For example, it can be used in colored concrete, barn paint, coatings and bricks.

After the full-scale facility is built at Sunday Creek’s Truetown discharge in Millfield, the plan is to examine how the process can be tweaked to capture aluminum. Like iron oxide, aluminum is found in high concentrations in AMD-impacted water and it has a healthy resale potential.

The paint pigment project received $3.5 million in Abandoned Mine Land Pilot Program funding from the US Department of the Interior’s Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement bureau.

The project’s collaborators aim to raise the last $4 million needed to complete the full-scale facility at the Truetown discharge.

At the Truetown discharge site, 6,000 pounds of iron flow into the Sunday Creek each day, rendering seven miles of the creek devoid of life. “There are dozens of other discharges across Appalachia that have similar flows,” Shively says.

Although the full-scale facility will only create four to six jobs, it will double the payroll for the zip code.

“Our philosophy is people, planet and profit – and all of those are on an equal footing,” Shively says. “[For us] this project epitomizes all of that,” she added, noting that Rural Action is committed to hiring locally.

Efficient data centers

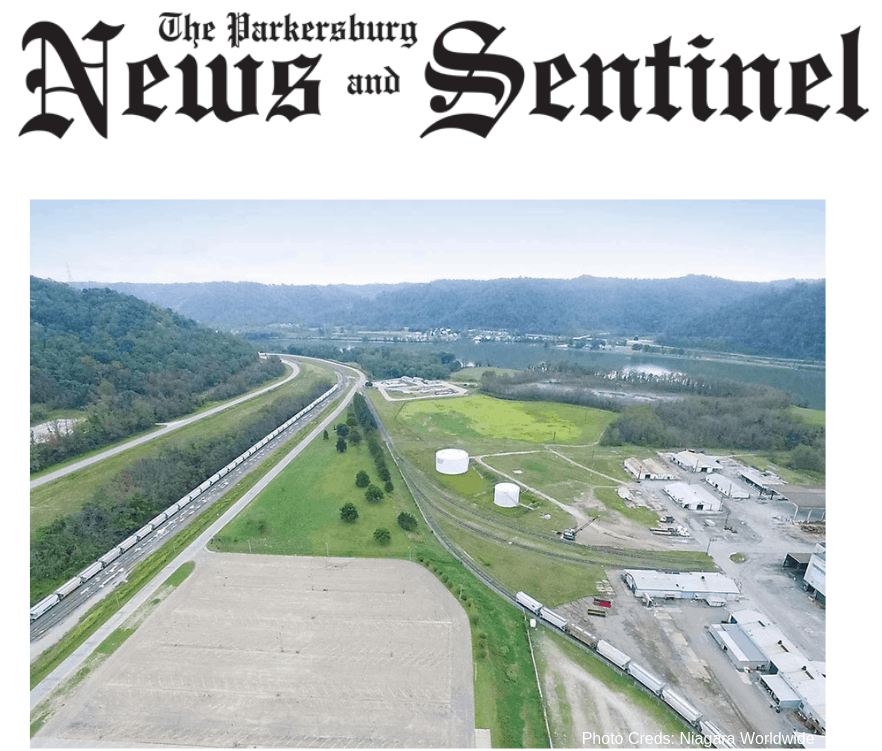

A solar-powered sustainable data center is expected to debut in Wise County, Virginia early next year. The hope is that the Mineral Gap Data Center’s project can offer other coal-impacted communities in Appalachia a roadmap for developing similar projects on abandoned surface mines (aka strip mines) as they attempt to diversify away from coal.

“More and more, we’re hearing from companies across the private sector who understand that solar can help them communicate their values, meet their energy needs, and have a positive impact on their bottom line,” says Devin Welch of Sun Tribe Solar.

The project also means that 3,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide is not released into the air each year, says Chelsea Barnes of environmental group Appalachian Voices. “[That’s] the equivalent of the carbon sequestered by more than 3,700 acres of US forests in one year or avoiding the burning of more than 360,000 gallons of gasoline,” she pointed out.

Additionally, the project’s annual land lease, as well as its annual site operation and maintenance activities, is expected to generate about $1,185,000 for the Wise County Industrial Development Authority and for local operation and maintenance contractors over the project’s 35 year-lifespan.

The project’s partners also plan to work with Mountain Empire Community College to help students visit the site to get hands-on experience when annual inspections are performed, and they plan to let Wise County Public School students schedule site visits to learn about a different energy resources in their area.

The new solar project for the private-sector data center operator, Mineral Gap Data Centers, is being partially funded through a $500,000 grant from the Abandoned Mine Land Pilot Program grant. Charlottesville-based Sun Tribe Solar, Appalachian Voices and Mineral Gap Data Centers jointly developed the project with support from the Wise County Industrial Development Authority and the Solar Workgroup of Southwest Virginia.

The twin aims of the solar-powered data center project are to remediate a barren mine site and to lure corporations and government entities with renewable energy goals – and large data needs – to the region as employers.

Increasingly, underutilized former mine areas in Appalachia are catching the eye of large-scale solar developers with track records of repurposing environmentally-challenged properties like landfills and brownfields.

“We are very interested,” says Chad Farrell of Encore Renewable Energy, adding that his Vermont-based company is exploring opportunities to develop utility-scale solar projects on coal ash ponds in Appalachia.

“This market opportunity is becoming more and more interesting due to the confluence of lower solar equipment pricing – as a result of continued technological advancements – with the increasingly challenged economics of fossil fuel-generated electricity, which is mainly derived from uncertain future fuel costs,” he says.

From a geo-technical standpoint, coal ash ponds are tricky to develop as solar fields, but they can be well suited to solar installations because they generally offer open, unshaded land in locations with robust electrical infrastructure, which can aid transmission.

Coal ash ponds are engineered structures that fossil fuel-based power stations use to dispose of industrial waste.

According to a Downstream Strategies’ study, under an aggressive solar development scenario, utility-scale installations in southwestern Virginia over a 10-year period could support about 212 jobs – including project development and onsite jobs, supply chain jobs, and induced jobs.

Local food markets

The construction of a solar-operated aquaponics facility in Kermit, West Virginia is set to begin next year. Lettuce and tilapia are on the menu.

“We are trying to build a central Appalachian food system,” says Sprouting Farms’ Boettner, who notes that West Virginia’s transition from an extraction-based economy has been a difficult one.

Boettner’s involvement in the project is fortuitous because he can draw upon the knowledge and contacts that he has built up through the creation and development of Sprouting Farms and the Turnrow Farm Collective. Together these local initiatives aim to help West Virginia farmers achieve greater financial success at farming by creating food hubs that process, market, distribute and sell locally-grown food, through equipment sharing opportunities, and through workforcetraining in high-tech farming techniques.

“Right now, we are trying to develop the market for lettuce and tilapia,” Boettner says. Schools are a particular focus.

As a sponsoring partner, Sprouting Farms will operate the aquaponics facility during its first two years of operation and possibly beyond. The hope is that from there the project can be replicated at other abandoned mine sites. The bulk of the $3.5 million in Abandoned Mine Land Pilot Program funding that the project received will go toward capping dangerous open mine portals in Kermit.

The project carries a higher price tag than future projects would because of the extent of environmental remediation required and the fact that the project tests a new idea.

Refresh Appalachia and the Mingo County Redevelopment Authority initiated the aquaponics project, and Boettner worked with Wisconsin-based Nelson & Pade Aquaponics to design and develop the aquaponic system.